University of Bristol

Department of Historical Studies

Best undergraduate dissertations of

2022

Catrin Woodcock

Oz Magazine: The gender politics of the

British counter-culture and the

construction of the ‘counter-cultural

woman

The Department of Historical Studies at the University of Bristol is committed to the advancement of historical knowledge and understanding, and to research of the highest order. Our undergraduates are part of that en deavour.

Since 2009, the Department has published the best of the annual dissertations produced by our final year undergraduates in recognition of the ex cellent research work being undertaken by our students. This was one of the best of this year’s final year undergraduate disserta tions. Please note: this dissertation is published in the state it was submitted for examination. Thus the author has not been able to correct errors and/or departures from departmental guidelines for the presentation of dissertations (e.g. in the formatting of its footnotes and bibliography).

© The author, 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author, or as expressly permitted by law. All citations of this work must be properly acknowledged.

28/04/2022 1906893

Oz Magazine: The gender politics of the British counter-culture

and the construction of the ‘counter-cultural woman’

1969, University of Wollongong Archives,

https://archivesonline.uow.edu.au/nodes/view/4847 (p.1).

28/04/2022 1906893

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Sarah Jones, who has been incredibly supportive and encouraging throughout this process. Her calm attitude was instrumental in allowing me to achieve my best.

28/04/2022 1906893

Table of Contents:

Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Literature: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Methodology and Terminology: ………………………………………………………………………………….

Dissertation Structure: ……………………………………………………………………………………………..

Chapter 1: Play Power and the ‘Hippy Chick’ ………………………………………………………..

Play power: a revolutionary ideology………………………………………………………………………….

‘She’s been fucking since she was 16’ …………………………………………………………………………

Chapter 2: The Visual Rhetoric of Sexuality ………………………………………………………….

Chapter 3: ‘Cunt Power’ with Germaine Greer ………………………………………………………

Alternative Approaches: Second-wave feminism …………………………………………………………

Conclusions …………………………………………………………………………………………………….

28/04/2022 1906893

Introduction

‘Chicks used to rub themselves up and down the seat arms in cinemas- and that was great’1

The above quote is taken from the 23rd edition of Oz London, colloquially known as Oz, from an article that discussed ‘putting the orgasm back into rock and roll’. Articles of this sort were a key feature of Oz, covering topics ranging from the politics of the New Left to sex and drugs. Richard Neville and fellow Australian Martin Sharp moved to London to set up Oz in 1967, after the Australian version saw them narrowly avoid jail time for obscene language and content, a problem that would follow them into their next publication.2 Combining satire with psychedelics and fun, this new magazine provided a guidebook to the alternative society from 1967 to 1973.

Oz was a product of the 1960s, a time of mass affluence, full employment, and technological development. Within this context, it has been argued that a sexual revolution took place.3 In Britain, this has been characterised as the ‘Swinging Sixties’ and roughly began in 1966.4 Political and cultural contexts allowed a proliferation of legislation that promoted sexual freedom and permissiveness: birth control was more readily accessible, abortion was legalised, and divorce became more widely available.5 For Hera Cook, there was an ‘astonishing pace of change’ as the sixties became a time of sexual freedom and celebration.6

1Author unknown, ‘Phil Ochs/Deviants/Pink Fairies music culture commentary’, Oz Magazine, September

1969, (pp.34-35).

2Simon Rycroft, Swinging City: A Cultural Geography of London, 1950-1974, (London: Routledge, 2011),

p.121.

3Example of this argument: Hera Cook, The Long Sexual Revolution: English Women, Sex and Contraception,

1800-1975, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

4Lesley Hall, Sex, Gender and Social Change in Britain since 1800, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000).

5Matt Cook, ‘Sexual Revolution(s) in Britain’ in eds. Gert Hekma and Alain Giami, Sexual Revolutions,

(Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), p.121.

6H. Cook, p.293.

28/04/2022 1906893

Within these larger changes, a division began to form as a new generation rejected the ways of their parents and looked to find new mentors.7 The result of this search saw the formation of an alternative society termed by Theodore Roszak as ‘the counter-culture’. 8 Difficult to define due to its broad array of concerns, ‘the counter-culture meant different things to different people at different times’; it was ‘the spirit of the times’.9 Ideologically speaking however, despite its variety, the counter-culture was a rejection of the dominant society, challenging cultural attitudes towards, amongst other things, sex, race, drugs, and politics.10 Its complexity can make it difficult for the researcher to characterise, fortunately, its ideology and their manifestations were documented extensively by the underground press.

The underground was the expression of this alternative society, largely consisting of non-profit publications created to serve their community that were produced both with and for their readership.11 The history of the underground press in Britain began in 1966 with the publication of International Times (It), soon followed in 1967 with the birth of Oz, which would become one of the most prolific publications within the counter-culture.12 The attitudes and opinions in Oz were consumed by an extensive portion of the alternative society, making it a central aspect of the underground.

This dissertation uses Oz magazine as a case study for understanding the gender politics of the underground and the constructions of female sexuality that permeated counter-cultural circles. With this, it will add to wider debates about 1960s Britain, presenting a more nuanced argument against a singular unified sexual revolution and suggesting that liberatory attitudes towards sex

7Barry Miles, ‘Underground Press’, British Library, (May 2016). https://www.bl.uk/20th-century

literature/articles/the-underground-press [Accessed 12 February 2022] (para. 11 of 14)

8Theodore Roszak, The Making of a Counterculture, (London: Faber and Faber, 1970), p.15.

9Elizabeth Nelson, British Counter-Culture 1966-73: A Study of the Underground Press, (London: Macmillan

Press, 1989), p.ix-8. Ebook.

10 Nelson, p.8.

11 Ibid.

12 Rycroft, p.121.

28/04/2022 1906893

seen within the counter-culture were in fact limited by the framing of female sexuality within the ‘male gaze’.13 It will demonstrate the complexity of the sexual revolution and the variations and limitations with which it took place, discussing how a sexual revolution that incorporated women was envisioned in various ways, once again demonstrating the multi-faceted nature of the sexual revolution in reality.

Literature:

The history of Britain in the 1960s has been the subject of considerable analysis in recent years with debates over why and how a sexual revolution took place dominating discussions of the period. However, a consideration of the impact on and role of the counter-culture in this revolution has largely remained invisible in the historical scholarship, leaving a significant section of British society in this period unexplored.14

This dissertation will contribute to literature that discusses the sexual revolution and its manifestations. The works of Hera Cook and Jeffrey Weeks seek to map the developments of the sexual revolution, debating concepts of ‘long revolutions’ or ‘permissive moments’ in order to understand the place of the sixties in British history.15 However, as Dominic Sandbrook has identified, in their efforts to categorise this period these histories often resort to stereotyping decades, limiting understandings of the complexities of the revolution that they argue for.16 More theoretical works such as Stephen Garton go some way in addressing this, exploring the

13 Edward Snow, ‘Theorizing the Male Gaze: Some Problems’, Representations, 25, (1989), 20-41.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2928465

14 Exceptions include historians of gender and the counter-culture in the US: Rochelle Gatlin, ‘Women and the

1960s Counter-culture’, in American Women since 1945, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1987).

15 H. Cook, pp.1-340; Jeffrey Weeks, Sex, politics and society: the regulation of sexuality since 1800, (NY:

Routledge, 1989).

16 Dominic Sandbrook, White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties, (NY: Little, Brown And

Company, 2006), p.xvii.

28/04/2022 1906893

concept of the multiplicity of sexual revolution(s). 17 His suggestion of the ‘two faces’ of what he terms ‘the second sexual revolution’ is particularly insightful.18 This dissertation will expand on his recognition of the limitations of even the most genuine attempts at sexual revolution suggesting that Garton’s ‘first face’ of revolution, categorised by masculine assumptions, was in fact the limiting factor in the ‘second face’ of true sexual liberation. David Allyn’s focus on the ‘double sexual standard’ has also been particularly influential as he too recognises the different manifestations of a sexual revolution although his central focus on America can lead his claims to be rather narrow.19

Perhaps the broadest array of scholarship in this area discusses the second-wave feminist movement, citing it as evidence of the failures of the sexual revolution; the works of Sheila Jeffreys and George Frankl are of note in this area.20 Other scholars have focused on the divides within the second-wave feminist movement based on disagreements surrounding sexuality; this section of the literature is particularly focused on feminist approaches to pornography, encapsulated in the contemporary works of radical feminists such as Kate Millett.21

Increasingly, there has been a recognition of the variety of opinions within the second-wave feminist movement particularly towards female sexuality, this development will be continued within this dissertation.

Very few histories of the sexual revolution in the context of the counter-culture exist, Angela Smith’s Re-reading Spare Rib is a notable exception as she combines a focus on second-wave

17 Stephen Garton, Histories of Sexuality, (London: Routledge, 2004), p.222. Ebook.

18 Ibid.

19 David Allyn, Make Love, Not War: The Sexual Revolution an Unfettered History, (London: Routledge, 2000)

20 Sheila Jeffreys, Anticlimax: a feminist perspective on the sexual revolution, (NY: Washington Square, 1991);

George Frankl, The Failure of the Sexual Revolution, (London: Open Press Gate, 2003).

21 Kate Millett, Sexual Politics, (NY: Garden City, 1970).; For a summary: Jeska Reeks, ‘A Look Back at Anger:

The Women’s Liberation Movement in 1978’, Women’s History Review, 19.3, (2010), 337-356.

DOI:10.1080/09612025.2010.489343

28/04/2022 1906893

feminism with an analysis of the counter-culture, recognising the influence of the underground’s approaches to sex in the development of the second-wave feminist movement.22 Much of the literature written on the underground more generally was produced by those who participated in its development; as such they can be seen as reminiscent and congratulatory. Confusing the objective for sexual liberation with the reality, they are often heavily reliant on first-hand accounts, conflating primary and secondary sources and thereby limiting analysis. Jonathon Green’s All Dressed Up: The Sixties and the Counterculture exemplifies this; his fond recollection of the period inhibits his analysis resulting in a failure to consider the sexism of the counter-culture.23

These works are important contributions but remain restricted by their lack of an analytical approach. Elizabeth Nelson’s British Counterculture 1966-73: A Study of the Underground Press avoids the complications of lived experience but its narrow focus on the political vision for the alternative society leads her to make broader claims on attitudes towards sex.24 She suggests that the counter-culture advocated for ‘freewheeling sexuality’, reflecting the broader trends in the historiography of 1960s Britain at the time of writing in 1989.25 Simon Rycroft’s more recent Swinging City: A Cultural Geography of London, 1950 1974 provides part of the solution to this problem as he recognises the inconsistencies in its representations of sexuality, exemplified by the ‘rape fantasy’ of the counter-cultural motto ‘dope, rock and roll and fucking in the streets’. 26

This is in line with wider trends in gender history which have increasingly focused on female agency.27 However, Rycroft’s focus on mapping London’s culture fails to recognise the importance of this argument to wider debates about the sexual revolution with his wide scope isolating him from the historiography of the

22 Angela Smith, Rereading Spare Rib, (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017).

23 Jonathon Green, All Dressed Up: Sixties and the Counterculture, (London: Jonathan Cape, 1998).

24 Nelson, pp.1-181.

25 Nelson, p.26.

26 Rycroft, p.122.

27 Dr. Joanne Bailey, ‘Is the rise of gender history “hiding” women from history once again?’, History in Focus,

8, (2005). https://archives.history.ac.uk/history-in-focus/Gender/articles.html [Accessed 25 March 2022]

counter-culture. Richard Deakin and Gerry Calin follow a similar line of thinking recognising the sexism but prioritising other analysis.28 Overall, although there has been an increasing recognition of this aspect of the counter-culture, no detailed analysis of the gender politics and representations of female sexuality has been conducted. This dissertation recognises this gap in the literature, providing an analysis of counter-cultural attitudes towards sexuality which can contribute to wider debates about the reality of the sexual revolution, deepening our understandings of the complexity and multiplicity of attitudes towards sex within Britain in this period.

28/04/2022 1906893

Methodology and Terminology:

When referring to the alternative society in this period the term ‘counter-culture’ has been chosen over ‘underground’ by some historians as it draws attention to this being a distinct category within society, this dissertation will recognise this, favouring ‘counter-culture’ and utilising ‘underground’ largely when discussing the underground press.29 The phrase ‘straight society’ is used to describe the cultural attitudes to which the counter-culture was opposed, as recognized by the literature.30

A consideration of sexuality is important for this study, this dissertation considers that sexuality is conceptualised with particular relation to social representations, sexuality in this context then is taken to be a construction, being more about social expectations and influence than inner

28 Richard Deakin, ‘The British Underground Press, 1965-1974’, (MA Dissertation, Cheltenham and Gloucester

College, June 1999). https://eprints.glos.ac.uk/8544/7/Deakin-British-underground-press.pdf; Gerry Carlin,

‘Rupert Bare: Art, Obscenity and the Oz trial’ in Marcus Collins (ed.), The Permissive Society and Its Enemies

(London: River Oram Press, 2007).

29 Chris Atton, ‘Counter-culture and Underground’, in eds. Andrew Nash et al. The Book in Britain,

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), p.648. Ebook.

30 Nelson, p.8.

28/04/2022 1906893

desires.31 It argues that the representations of women within the pages of Oz were influential in constructing societal norms for female sexuality, framing it to be more accessible to men.

The source base for this dissertation focuses on Oz magazine itself, all 48 issues of the magazines are available online through the University of Wollongong Collection.32 The collection has been instrumental in allowing a unique analysis to establish a more complete picture of the gender politics of Oz. The magazines, in their rhetoric and content, serve as evidence of the construction of an acceptable form of female sexuality which this dissertation has termed the ‘counter-cultural woman’, this idealised construction framed female sexual liberation under the constraints of the ‘male gaze’ limiting its true liberation.

To supplement the magazines and to provide context to the editorship and formulation of Oz, oral accounts in the form of John Green’s Days in the Life interviews have been used to recognise the agency of the men and women who edited and wrote the magazine and were part of the British counter-culture.33 These interviews offer a unique perspective from the creators of Oz magazine and their close associates and, with hindsight at their disposal, the interviewees suggest a growing recognition of sexism within this period. The interviews are in part self congratulating and of course are subject to distortion of memory, but despite this, they are useful in gauging opinions of those directly involved in the production of the magazine and contextualising its ideology, providing insight where other sources cannot.

The testimony of women who participated within the counter-culture were also particularly useful in confirming that the construction of female sexuality present within the pages of Oz was also relevant

31 As discussed in: Stephen Seidman, The Social Construction of Sexuality, (NY: WW Norton, 2003).

32 University of Wollongong Archives, ARC 052/48, Oz London Collection (1967-1973).

https://archivesonline.uow.edu.au/nodes/view/3495 [Accessed December 2021- April 2022]

33 Jonathon Green, Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground 1961-1971, (Reading: Cox and

Wyman, 1988).

28/04/2022 1906893

outside of them as they had direct experience with the reality of the sexual revolution. Additionally, Neville’s Play Power was used as a reference for the attitudes of the main editor of the magazine at the time of its publication, his own experiences and descriptions of women confirm the sexist attitudes that this dissertation argues are present in Oz.34

The analytical framework suggested by Mehita Iqani in his work on consumer magazines will inspire the critical analysis of Oz, considering the ‘multimodality’ of magazines including the ‘visual and verbal, texture and materiality, space and lighting’ that all combine to construct meaning.35 His linguistic analysis and critical visual analysis will be combined as a way of understanding the construction of female sexuality created through Oz’s ‘multimodal’ elements.36 Iqani also points to the influence of the context within which magazines are created, a contextualisation is integral to a thorough analysis and will be recognised through a consideration of editorial power. This methodology has been chosen due to its all encompassing considerations. The nature of Oz and the importance of language, context, and imagery are all fundamental aspects to understanding how it represented attitudes towards female sexuality within the underground, Iqani’s methodology is therefore a fitting way to consider the sources.

This dissertation uses Oz magazine as a case study for understanding attitudes towards female sexual liberation within the wider counter-culture, arguing that the opinions seen within its pages were also reflective of views within the counter-culture more generally. The underground press was an interconnected network of journals and magazines that all fed off each other forming the ideology of the counter-culture; the rhetoric of Oz then, is representative

34 Richard Neville, Play Power, (London: Jonathan Cape, 1970).

35 Mehita Iqani, Consumer culture and the media, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p.41.

36 Ibid.

28/04/2022 1906893

not just of Oz and its readership, but of many more of the underground publications produced in this period as well.37 For Nelson, ‘the underground press serve[d] as the major repository of counter-cultural views and visions’ giving the movement a sense of identity and unity.38

Additionally, Deakin suggests that the underground press acted as an archive for the social history of the counter-culture, confirming the relevance of Oz as a case study for understanding wider counter-cultural attitudes towards female sexual liberation.39 Rycroft suggests that Oz in particular represented the ‘“popular” hippy underground’ which he asserts was the ‘strongest and most influential faction of underground London’, clearly then the underground press and Oz specifically is a fitting case study for understanding counter-cultural attitudes towards

female sexuality.40

Marshall McLuhan’s media theories further confirm the importance of magazines to understanding culture. He suggests that magazines with a ‘multi-media experience’, as is present in the combination of articles and imagery in Oz, are dialogic and have an impact on readers as much as readers have on the magazines, they are therefore socialising agents.41 The construction of female sexuality presented by Oz can therefore be seen as influential in shaping and reflecting attitudes outside of the magazine as well.

Dissertation Structure:

This dissertation argues that the attitudes towards female sexuality presented in the pages of Oz magazine, seen as reflective of the wider counter-culture, were limited in their liberation. The presentation of female sexuality is subsumed by the ‘male gaze’, resulting in the construction of the idealised ‘counter-cultural woman’ that presented as a sexual object for

37 AnnMarie Brennan, ‘An Architecture for the Mind: OZ Magazine and the Technologies of the Counterculture’,

Journal of Design Studies Forum, 9.3, (2017), 323. DOI:10.1080/17547075.2017.1368828

38 Nelson, p.47.

39 Deakin, p.3.

40 Rycroft, p.121.

41 Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The extensions of man, (NY: McGraw-Hill, 1964), p.176.

28/04/2022 1906893

male pleasure. This poses a challenge to wider perceptions of a singular sexual revolution in

the 1960s.

Chapter one will explore the language and rhetoric presented in Oz magazine to understand how discussions of women within the articles aided in the construction of the ‘counter-cultural woman’ that idealised female sexuality to be more accessible to men. It will demonstrate that the rhetoric of Oz did not display the ‘free love’ that Neville aspired to.42 Chapter two will focus on the sexualisation of the female form through representations of women in Oz, analysing the general imagery presented throughout the magazine issues. This section argues that the objectification of female bodies in Oz, influenced by the ‘male gaze’, further aided in the construction of female sexuality as a commodity. Chapter three will focus on the ‘Cunt Power’ issue of Oz, which discussed the growth of feminism in this period, demonstrating the role the counter-culture played in motivating feminist reactions to the sexual revolution further emphasising its limitations and the variations of attitudes towards sex. Overall, representations of ‘the counter-cultural woman’ within Oz are argued to demonstrate the construction of female sexuality framed within the male vision for female sexual liberation and can be seen as representative of wider trends of gender politics within the counter-culture in the 1960s.

42 Neville argued that Oz aimed to abolish sexual guilt: Neville cited by Tony Palmer, The Trials of Oz: The

Longest Obscenity Trial in History, (London: Lume Books, 2021), p.88.

28/04/2022 1906893

Chapter 1: Play Power and the ‘Hippy Chick’

This chapter will consider the content of Oz magazine, beginning with a discussion of Neville’s personal ideology in order to contextualise the production of the magazine and note the role of editorial power. It will then focus on representations of women within the language of Oz employing a linguistic analysis in order to understand how the vision for the ‘counter-cultural woman’ is constructed. It will argue that discussions of women within Oz constructed a form of female sexuality framed within male ideals of femininity in which women were increasingly considered sexual objects.

Play power: a revolutionary ideology

In 1970, Richard Neville published Play Power, his personal account of the inner workings and philosophies of the underground.43 Centred around an enjoyment of life, Neville’s philosophies employed a form of hedonism in which play is prioritised over work.44 For Neville, this form of play manifested into what is now viewed as the rape of a 14-year-old girl whom he describes as both ‘moderately attractive’ and ‘cherubic’.45 Although in hindsight he has expressed regret over this decision, his unapologetic presentation of the events in Play Power gives important insight into the mindset of the main editor of Oz and provides context to the representations of women throughout. Acknowledging Iqani’s emphasis on contextualising magazines, Neville’s philosophy, as summarised by Jim Anderson, that ‘the

43 Neville, Play, pp.1-325.

44 David Buckingham, ‘Children of the Revolution? The counter-culture, the idea of childhood and the case of

Schoolkids Oz’, Strenæ online, 13, (2018). https://doi.org/10.4000/strenae.1808 (para. 8 of 51)

45 Neville, Play, p.60.

28/04/2022 1906893

way to a girl’s mind is through her cunt’ is particularly indicative of his approach towards

female sexuality and highlights the editorial attitudes towards women.46

Neville worked alongside the likes of Felix Dennis and Anderson, combining their expertise to create Oz. Rycroft has suggested that the complex interaction between editors created a ‘loose editorial policy which resulted in a hollow rhetoric’.47 However, this dissertation argues that Oz did not seek to provide a cohesive argument but instead wished to represent the multitude of attitudes and opinions within the counter-culture. The prevalence of sexist representations of women that this dissertation argues are seen throughout the variety of contradictory and confusing ideologies, is therefore indicative of a broader attitude towards female sexuality. In this respect, the arguably contradictory nature of Oz serves to emphasise the over-arching sexism that was present throughout multiple aspects of the counter-culture.

‘She’s been fucking since she was 16’48

The personal ideologies of the editors are clear within the language and rhetoric presented in Oz, the objectification and depersonalisation that the magazine employed when referencing women illuminates the construction of acceptable forms of female sexuality. Oz almost exclusively uses derogatory terms that served to dehumanise the women discussed, displaying a lack of respect and failure to recognise them as individuals. One such example is seen in an article written by Felix Dennis which discusses Oz receiving an award from Blackhill Bullshit for ‘most obscene publication’. Dennis references ‘a beautiful and naked chick abusing herself’, not only utilising the derogatory term ‘chick’ but suggesting that she only deserves

46 Jim Anderson, ‘Remarks on 1968, Richard Neville and his book’, Counterculture Studies, 2.1, (2019), 30-42.

10.14453/ccs.v2.i1.13

47 Rycroft, p.121.

48 Ken Coates, ‘An Address to Politicians’, Oz Magazine, May 1967, (p.13).

28/04/2022 1906893

recognition due to her ‘acceptable’ appearance and her nudity, he constructs this woman’s validity based on her ability to fit into acceptable standards of femininity and her availability to men. This trend continues throughout almost the entire printing of Oz with references to women almost solely utilising language such as ‘chicks’, ‘birds’, ‘girls’ or ‘lovely ladies’. All these terms serve to belittle women, either through their objectification or through validation based on their appearances. In some articles the appearance of a woman is the sole purpose of her mention as is the case with John Coleman’s reference to ‘a large brown beautiful girl’ and ‘the blond strip of a girl’ in an article that discussed the role of cinema.49

Almost all mentions of women include descriptions of their appearance, in comparison, references to men describe them based on their personality or political ideology with entire articles discussing the politics of men such as Malcolm X.50 Furthermore, the general representations of women can be seen as both objectifying and vulgar as one article asks, ‘are you not embarrassed when you unstrap your wooden leg to fuck your wife?’.51 Although this satirical article is designed to attack the husband, it also presents women as subservient to men, suggesting that a man always has the right to ‘fuck’ his wife.

This kind of language can be found in every issue of Oz; placing women as subservient to men, it reduces them to their image and sexuality, constructing the idealisation of the ‘counter-cultural woman’ as a sexual object for men. Perhaps the most obvious objectification of women as sexual commodities is seen in Oz 26, in an article titled ‘Gangster of Love Deported’, a reprinting of extracts from Bill Levy’s journal. Levy was a prolific character in the underground and although he worked for rival magazine It the diary entries present an attack on the prudishness of the establishment as they detail Levy’s experience in jail after his arrest for his involvement in the sex-magazine Suck, by republishing

49 John Coleman, ‘Sexulloid Sickness’, Oz Magazine, April 1968, (p.29).

50 Unknown author, ‘RAAStus: WI in W.2 Collin MacInnes’, Oz Magazine, February 1967 (p.14).

51 Angelo Quattrocchi, ‘Yesterday I subscribed to the New Statesman, today I am just, reasonable & dead’, Oz

Magazine, April 1968, (p.26).

28/04/2022 1906893

them Oz was showing support to Levy. With this in mind, we can take his representations of women as being agreeable to the editors of Oz, particularly when viewed in conjunction with other articles, as they readily printed Levy’s sexist descriptions. On the second day of his incarceration, Levy reminisces about his sexual experiences of the past two weeks: Sex with Susan is cosmic.

In many ways, Abby performs better, but our sex life has been a disaster. […] Thinking about cunt: Abby’s and Susan’s. […] Can’t keep my mind off cunt. Abby can use her cunt muscles like a firm handshake pumping out the last drop of sperm. Susan’s cunt is warm and moist.52

Belittled as sex objects and yet celebrated for this exact reason, this article emphasises the construction of the ‘counter-cultural woman’. The comparison of these women’s abilities, and their genitalia more specifically, indicates their treatment as sexual objects for male pleasure and demonstrates the framing of female sexuality within the idealised male vision of female sexual liberation. Presented like a review, this section represents women as perpetually available to give men pleasure, demonstrating that the ideal ‘counter-cultural woman’ is both sexual and submissive. The comparison of the two women further exemplifies their construction as objects, identified not by their personality, but in this case by their genitalia, their sexuality is clearly constructed as a commodity.

Similarly, Oz 18 presents us with evidence of the continuation of the ‘sexual double standard,’ within the counter-culture.53 In an article written by Neville he discusses his trip to Marrakesh and his meeting with Lea Heater, the organiser of the ‘love in’ Neville was attending. Neville’s

52 Bill Levy, ‘Gangster of Love Deported’, Oz Magazine, February 1970, (p.21).

53 R. R. Milhausen MSc and E. S. Herold PhD, ‘Reconceptualizing the Sexual Double Standard’, Journal of

Psychology & Human Sexuality, 13.2, (2002), 63-83. DOI:10.1300/ J056v13n02_05

28/04/2022 1906893

article typifies the treatment and representations of women within Oz magazine, and it is fitting that the article is written by its primary editor and creator. His interactions with women throughout his trip demonstrate the construction of the ‘counter-cultural woman’ as depersonalised and objectified: Neville omits addressing a single woman in his recollections by their name, instead he describes ‘two exotic witches’, ‘the blonde Texan lady’, and ‘the whale-like Moroccan prostitute’ who is later described as the ‘grinning maiden who lumbered towards [his] petrified genitals’.54

All of these descriptions illustrate the objectification of women, their appearances become their identity and Neville links their relevance in the article to their sexuality, justifying their presence in the story through both their appearances and sexual allure.

For the ‘witches’ their exoticness is tantalising; the lady from Texas is celebrated for her perpetual nudity; the prostitute’s occupation already makes her worthy of mention, and her description solidifies her undesirability and therefore lower value. In this way, Neville clearly illustrates attitudes towards women within the counter-culture as conceptualised based on sex and looks. His final description of the Moroccan prostitute exemplifies the construction of female sexuality as inherently available, making her seem sex-crazed, he describes how the woman throws herself at him and his suggestion that he is scared and yet intrigued places him as the desirable and the woman as the object for his pleasure. In this way, the article exemplifies the construction of female sexuality within the pages of Oz, depicting woman as depersonalised objects whose value lies in their appearance and whose sexuality is the commodity of men.

These articles are typical examples of the general treatment and attitudes towards women within the pages of Oz magazine, each issue of Oz aided in the construction of the idealised image of the ‘counter-cultural woman’, framing her sexuality based on the male ideal. Nicola

54 Richard Neville, ‘What Paul Getty, the Freak Horseman of the Djmaa El Fna Did Last Month’, Oz Magazine,

February 1969, (p.22).

28/04/2022 1906893

Lane, cartoonist for It magazine, has suggested that ‘from a girl’s point of view the important thing to remember about the 60s is that it was totally male-dominated. […] You were there really for fucks and domesticity.’55 Lane was heavily involved with the underground and her recognition of the sexism present serves to confirm the arguments of this dissertation, her experiences demonstrate that the rhetoric of female sexual liberation within the articles of Oz also reflect the reality of life for women in the period as well.

Articles such as those written by David Widgery seem to challenge the constructed version of female sexuality presented within much of Oz. Many of Widgery’s articles are refreshingly critical of the ideology of Oz, focusing on topics ranging from politics to sexual suppression.

According to Rycroft, Widgery felt that ‘London’s counterculture and specifically the Ozniks had chosen style over value’, attacking the government ‘where it likes, not where it hurts’.56 Widgery saw the limitations of the counter-culture that were exemplified through the pages of Oz, and as a result wrote intellectually critical articles for the magazine to draw attention to these issues. However, the design of Oz, including the typography and imagery was used to subvert his messages, undermining his critiques.

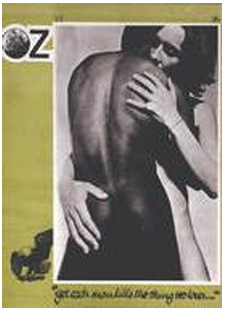

Widgery’s article on the entrapment of the hippy chick is particularly relevant to our discussion as his assertions on her lack of freedom presented a case for women being ‘doubly enslaved’ by both capitalism and men. However, the article was transposed with an image of a bi-racial couple embracing, not only distorting the wording but distracting from it altogether.57 Through subtle means, the editors of Oz undermined Widgery’s New Left ideological claims. On other occasions, satirical cartoons and sexualised images were used to the same end.58 Clearly, even

55 Nicola Lane cited by Green, Days, p.401.

56 Rycroft, pg.135.

57 David Widgery, ‘Played-out’, Oz Magazine, February 1970, (p.44).

58 For more examples see: Oz Magazine, February 1970, (pp.18-19); December 1968, (p.28).

28/04/2022 1906893

articles that presented a form of more ‘genuine sexual liberation’ and a criticism of the constructed female sexuality commonly presented within Oz were subverted through design, presenting the readership with a mockery of its messages, and thereby undermining any real challenge to the dominant philosophy within the magazine. The construction of the ‘counter cultural woman’ and the idealisation of female sexuality therefore remained conclusively sexist throughout the articles of Oz as even opposing messages were subverted to prevent any real challenge to the dominant ideas. The testimony of Lane alongside the established role and position of Oz in the counter-culture confirm that this construction was relevant outside of the magazine as well.

28/04/2022 1906893

Chapter 2: The Visual Rhetoric of Sexuality

This chapter will focus on the visuals of Oz, considering how representations of women within the images and advertisements in the magazine reinforced the messages perpetuated through the articles, further constructing female sexuality as the commodity of men. The imagery presented in Oz established expectations for female sexuality through its representation of the female form; using depictions of female nudity, Oz constructed an ideal of a sexualised, objectified women, transforming them from individuals into sexual objects. The chapter will begin with an analysis of the imagery presented in Oz, considering the concept of the ‘male gaze’ to explain this construction. Following this, an analysis of the advertisements in Oz will demonstrate how the magazine commodified the female body, converting women into objects to sell.

Overall, it will be shown that the visual rhetoric of Oz was instrumental in the construction of a distinct form of female sexuality that has been termed in this dissertation the ‘counter-cultural woman’, which perpetuated the ideal of a female sexuality that was readily available to men.

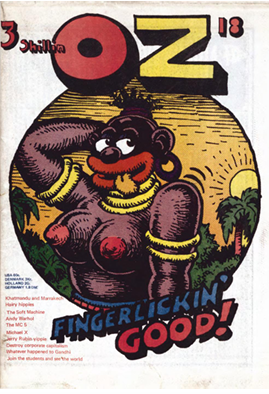

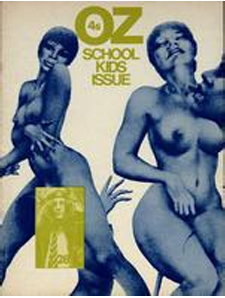

Oz sought to fill a gap in the market for a colourful magazine within the underground press, its visual strategy has been cited as one of the main reasons for its extreme popularity as it distinguished Oz from the other underground magazines.59 An analysis of the imagery is therefore equally as important as analysing content. Of the 48 magazine covers, 21 feature

female nudity.60 Only five covers feature male nudity, all of which are more modest than comparative images of female nudity with male genitalia covered in all examples (Figure 2).61

59 Brennan, p.323.60 Covers with female nudity: Oz Magazine, March, May 1967; February, June, August, October, December 1968;

July, December 1969; May, October, November 1970; February/March, April, July, December 1971; February,

April, May/June, September 1972; April, November 1973.

61 Covers with male nudity: Oz Magazine, September 1969; February, October 1970; January, November 1973.

28/04/2022 1906893

September 1969 (p.1).

Contrastingly, images of female nudity are both more explicit and more sexualised, the most provocative aspects of a woman, particularly her breasts, are accentuated through posing. Women on the covers, whether cartoon or real, face the readers with their bodies open and exposed to seduce them into purchasing and reading the magazine, the images hint at the women’s availability through their provocative presentation (Figure 1 and 3).

Magazine, May 1970, (p.1).

28/04/2022 1906893

When discussing the development of pornography in this period Marcus Collins argues that ‘poses sanctioned the male gaze while also suggesting that women nursed the same desires as men’. In this way he suggests that the magazines avoided presenting women as objects.

Although he focuses on the more explicitly pornographic magazines such as Playboy his assertion seems particularly relevant to Oz as its imagery could certainly be classified as pornographic.62 His assessment seems optimistic, he suggests that these images attempted to present women as willing sexual partners thereby liberating their sexuality, and yet he maintains that they were conforming to the ‘male gaze’ through their presentation and posing. This dissertation argues that any image in which a woman is forced to conform to the idealised ‘male gaze’ prevents her sexuality from becoming her own, her inability to express herself freely creates a female sexuality that remains subsumed by male assumptions and therefore unliberated.

Collins sees the move to presenting women as sexually available to be sexually liberation, when in reality it represents the construction of female sexuality as a male commodity. The sexualisation of the female form was readily used by Oz as a sales technique in order to ensure its success, and the female nude became one of the central images of Oz, repeatedly featuring throughout all issues. This should be considered with respect to the theory of the ‘male gaze’. As both the commissioners (in this case editors) and the majority of intended viewers, the tastes of men dictated the representations of feminine subjects, it is this concept that has been termed the influence of the ‘male gaze’. 63 Applying this theory in the context of Renaissance art, Benjamin Neiley sees that this has resulted in a dichotomy between presentations of women and men where images of women were an expression of an ideal

62 Marcus Collins, Modern Love, (London: Atlantic Books, 2004), p.151.

63 Snow, p.38.

28/04/2022 1906893

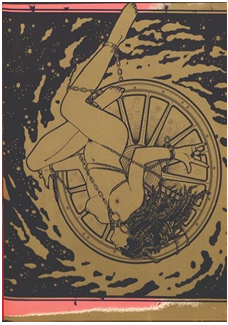

compared to men where they demonstrated a reality.64 A similar trend can be seen within the images and artwork found within Oz magazine as the female form was idealised and sexualised, constructing acceptable standards for female sexuality and beauty. Lynda Nead has proposed that within western culture the female nude should be seen as a form of regulation of women, we can suggest then that the presentation of the female body within Oz regulated acceptable standards for female sexuality. 65 The way in which femininity and female sexuality are constructed throughout Oz therefore informs the extent to which we may see a female sexual liberation. Keith Morris, photographer and contributor to Oz, has confirmed that the magazine used ‘decorative ladies or girls fighting in mud’ to bulk out the contents and entice its readership suggesting that the imagery did not seek to represent women as sexually free. 66 One such example is seen in Figure 4.

English, ‘Catherine and the Wheel of Fire’, Oz

Magazine, June 1968, (p.45).

64 Benjamin Neiley, ‘Female Nudity in Renaissance Art: Feminist Ethical Considerations’, Confluence, (2018).

https://confluence.gallatin.nyu.edu/context/first-year-writing-seminar/the-ethics-of-the-female-nude [Accessed

13 March 2022].

65 Lynda Nead, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality, (London: Routledge, 1992), p.8. Ebook.

66 Keith Morris cited by Green, Days, pg.153

28/04/2022 1906893

This image featured in Oz 13 as a pull-out poster titled ‘Catherine and the Wheel of Fire’. Issue 13 was themed around ‘the pornography of violence’ and we can suggest that the nude female is demonstrative of the pornography, and her restraints symbolise the violence the issue has considered. The woman’s figure is slender with her legs crossed, amplifying her curves, her breasts and lower genitalia are also drawn in detail drawing one’s gaze to these regions and sexualising her body for the viewer.67

Additionally, she faces away from the reader with no obvious expression on her face, this depersonalises her and reduces the readers ability to connect with the image. Her positioning suggests her sexual nature and her bonds imply that her sexuality is restrained, to set her free is therefore to earn her sexuality. Her beautiful figure and sexualised nature construct the image of the ‘counter-cultural woman’, implying her abundance of sexual desires and her availability.

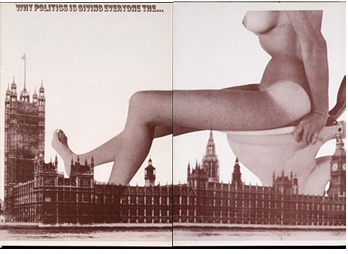

Similarly, Oz 3 features an image of a nude female body sat on a toilet over the Houses of Parliament designed by Mike McInney, part time designer for Oz (Figure 5). The image is designed to be an attack on politics and yet uses female nudity to emphasise its point. The woman’s legs are outstretched, elongating her figure and opening her body to be more visible, her breasts are also exposed readily confronting the viewer upon opening the double paged spread. Despite its title and her position on the toilet, the female body is still sexualised as the female form is manipulated to grab attention.68 The sexually provocative image presents women once again as sexual objects, the model’s face is cropped out, depersonalising her and confirming that she was being used only for her body. Although this image is less overtly sexual than other examples in Oz, the irrelevance of the nudity to the article is particularly

67 Figure 4.

68 Figure 5.

demonstrative of the over-use of the female body throughout the magazine and confirms the

representation of female sexuality as the commodity of men, to be utilised in a variety of ways.

Everyone the…’, Oz Magazine, May 1967, (pp.11-12).

Other images and cartoons are more explicitly pornographic, depicting vulgar illustrations of genitalia and sexualising and objectifying the female body. Female nudity came to typify Oz, its constant use served to reassert the oversexualisation of the female body, constructing an idealised form of female sexuality as more accessible to men, this significantly limited sexual liberation.69 The representations of female sexuality throughout the imagery of Oz propagated the view that the ‘counter-cultural woman’ was the commodity of the ‘counter-cultural man’; the centrality of pornography to depictions of women throughout the magazine solidified their construction as sexual objects. Chelsea Reynolds has contended that magazines can be seen to contribute to normative ideologies about sex, reinforcing stereotypes and forcing conformity.70

69 For more examples: Peter O’Donnell, ‘Modesty Blaise’, Oz Magazine, April 1968, (p.26) and Michael English,

No title, Oz Magazine, September 1968, (p.27).

70 Chelsea Reynolds, ‘The “Woke” Sexual Discourse’ in ed. Miglena Sternadori and Tim Holmes, The Handbook

of Magazine Studies, (New Jersey: Blackwell, 2020), p.181. Ebook.

28/04/2022 1906893

Representations of female sexuality, particularly the presentation of female nudity seen within Oz, were therefore influential in limiting female sexual liberation by establishing the construction of acceptable female sexuality within the counter-culture as its readership consumed the proliferation of women displayed as sex objects.

The advertisements within Oz confirm this further and are particularly demonstrative of this construction of the female body as a commodity, as they utilise female nudity for the express purpose of selling. Oz was not written for financial gain and used its advertisements as a main source of income. Magazines such as Oz existed only to serve their community and the editors made no more than the average person in this period, the advertisements were therefore another integral aspect of the magazine.71

The choice of advertisements and the imagery within them should therefore be an important consideration in our discussion. Most ads centred around the theme of sex, whether this be advertising for sex magazines or sex aids, they frequently used the female nude to appeal to the consumer, mostly with a target audience of men. Nelson has suggested that the irony of relying on commercial sex to finance Oz whilst advocating for sexual freedom was lost on the editors.72 In fact, Oz was the only magazine to have reciprocal advertising with Penthouse, an institution which Roszak criticised for conceptualising the woman as a ‘submissive bunny [and] a mindless decoration’.73 Much of the advertisements shown in Oz framed women in a similar fashion to the construction Roszak alludes to.

A frequent advert within the magazine advertised ‘MAGNAPHALL’, a successful way of ‘increasing the size of the male organ’.74 This advert in particular demonstrates the differences between displaying male and female nudity (Figure 6), while the woman’s breasts and face are

71 Miles, (para. 11 of 14).

72 Nelson, p.60.

73 Roszak, p.15.

74 Figure 6.

28/04/2022 1906893

clearly visible, the man is hidden within the female figure, with only his legs and arms clearly visible. Although the advert would clearly lend to an example of the product working, thereby suggesting a male nude would be more appropriate, instead the female body is used to attract attention. Once again, aligning with the other imagery within the magazine the female is presented as submissive to the man, she is sexually available and an object for male pleasure rather than an autonomous individual. In Oz 26, an advert for the same product exclusively features a female nude, this time even more explicit with both her breasts and bottom clearly visible in a suggestive and seductive pose.75 Her exclamation of ‘Yes!’ once again implies her availability, challenging the readers to miss out on an opportunity with a woman like her. The female nudity denies women autonomy over their own sexuality as the model adheres to the vision of acceptable female sexuality framed within the ‘male gaze’ (Figure 7).

Magazine, April 1970, (p.29).

Magazine, February 1970, (p.37).

28/04/2022 1906893

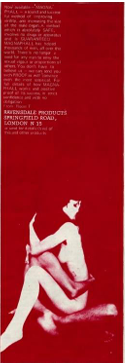

Similarly, an advertisement for SUCK magazine, a sex paper sold in Amsterdam, features a graphic female nude with her breasts exposed as she exclaims ‘Suck?’ suggestively.76 Using innuendo the advert engages the reader, specifically male readers, presenting the female body as an object to sell. The black and white tones accentuate the curves on the model’s body, manipulating the female form in order to sell the magazine. The female body is uncompromisingly used as a way to promote various sexual items, these women’s sexuality becomes their identity, and their autonomy is silenced by their conversion into a body rather than a person (Figure 8).

David Gauntlett suggests that advertisements are influential in shaping gender roles as they construct stereotypes of ideal standards and often result in ‘unrealistic expectation from one gender’.77 Evelyn Goldfield et.al have also suggest that, in general, ‘the advertising industry […] has helped to condition women to their secondary status.78 The advertisements of Oz depict women as sexually available and submissive to man, through these representations they

76 Figure 8.

77 David Gauntlett, Media, Gender and Identity, (London: Routledge, 2008), p.98.

78 Evelyn Goldfield, Sue Munaker, and Naomi Weisstein, ‘A Woman is a Sometime Thing’, in ed. Priscilla Long,

The New Left; a Collection of Essays, (Boston: P. Sargent, 1969), p.245.

28/04/2022 1906893

present idealisations of gender roles within the new counter-cultural society where women are readily assigned the role of sexual commodity. Many of the ads in Oz recurred throughout its printing meaning a focus on any edition of the magazine would result in a similar conclusion. This chapter has utilised a visual analysis of the images and advertisements within Oz magazine to demonstrate how representations of women as sex symbols continued throughout all aspects of the magazine, perpetuating the idealised image of the ‘counter-cultural woman’.

The imagery of Oz supplemented the articles in constructing the acceptable norms for women’s sexuality and they combined to prevent a true female sexual liberation. As we will see in the final chapter, leading female figures in the counter-culture and wider society were themselves convinced of the power of the female nude in constructing sexuality, a testament to the power of the imagery in Oz magazine and its influence within the counter-culture. This analysis of Oz therefore demonstrates the limitations to the sexual revolution as it has previously been conceived and the reality within which it took place.

28/04/2022 1906893

Chapter 3: ‘Cunt Power’ with Germaine Greer

This chapter will focus on the edition of Oz produced and edited by Germaine Greer, titled ‘Cunt Power’. The issue was themed around the growth of the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) and feminist ideas of a sexual revolution, it exemplifies the approach of controversial feminist Germaine Greer to including women in the sexual revolution and is a particularly interesting source for understanding the variety of perspectives on this topic. This chapter will focus on this issue’s messages and design to understand Greer’s vision.

It will then consider the approaches of other feminists of the period, concluding that despite the potential of Greer’s

ideas, their manipulation ensured that her version of the ‘counter-cultural woman’ was also subsumed by male ideals of female sexuality, preventing a true female sexual liberation. Greer’s earlier contribution in Oz 26 set the scene for the feminist issue of Oz (Oz 29), her article The Slag Heap Erupts discussed the current state of the feminist movement, critiquing it for its ‘solemn absurdity’.79 Her attack on the movement drew attention to their perceived incompetence as Greer criticised them for their inability to ‘to find any alternative to the phony concept of female sexuality as monogamy and child-bearing.’80 Her unorthodox approach aimed to reclaim female sexual licence more explicitly and forcefully thereby exposing the misogyny present throughout society. Greer sought to use her own body and pornographic images more generally to reclaim her sexuality in her own way, constructing a ‘powerful form of female sexuality’.81 For her, ‘a woman who cannot organise her sex life in her own interest is hardly likely to reorganize society upon more rational lines’.82 It was this message and the idea of female empowerment in a masculine dominated world that Greer attempted to convey

79 Germaine Greer, ‘The Slag Heap Erupts’, Oz Magazine, February 1970, (p.18).

80 Ibid.

81 Germaine Greer, The Female Eunuch, (Glasgow: Harper Collins, 1970) p.35.

82 Greer, ‘Slag’, February 1970, (p.18).

28/04/2022 1906893

throughout Oz 29. Her vision had the potential to provide the ‘genuine revolution’ which Garton discusses; however, her arguments were manipulated and rather than opposing sexual stereotypes only served to reinforce them.83

Oz 29 began with a drawing of female genitalia: unshaven, it presented a challenge to the ‘male gaze’ and its preference for hairless women, a clear attempt to regain control over female bodies. It continued with articles that followed a similar rhetoric, attempting to subvert patriarchal control over women. One such article discussed how to knit a ‘cock-sock’ linking a stereotypical female activity with female sexual desire.84

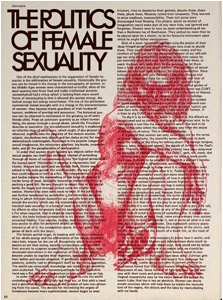

The magazine attempted to regain control of female sexuality by playing with established gender roles and subverting them by giving women sexual autonomy. Greer’s own article ‘The Politics of Female Sexuality’ featured an in-depth analysis of historical and contemporary constructions of female sexuality.85 She suggested that it is through the total obliteration of female sexuality that women are converted from sexual people to sexual objects. In order to combat this, Greer argues that ‘Skirts must be lifted, knickers must come off forever. It is time to dig CUNT and women must dig it first’. Her message was clear: love yourself, embrace your sexuality, and your sexuality will become yours once again. In practice it had the potential to provide a true liberation, in reality, patriarchal powers were too strong to overcome. Despite Greer’s fundamental role in editing this issue, her name features fourth in the credits section, after the likes of Anderson and Dennis, and she is credited with only her first name with her male counterparts receiving full names. In addition, many of the articles contained within this issue are rendered almost illegible by design and imagery, Greer’s article is superimposed onto a rather grotesque and haunting image of a dishevelled beast-like woman in the nude with her

83 Garton, p.222.

84 Greer, Oz Magazine, ‘The Politics of Female Sexuality’, July 1970, (p.5).

85 Greer ‘Politics’, (p.10).

28/04/2022 1906893

legs open (Figure 9). The image relates to Greer’s notion that a woman’s genitalia is not ‘rotting meat’ and yet it not only subverts the arguments put forward by covering the writing but also juxtaposes Greer’s words with an image of exactly what she denies.86 It is difficult to know if this was her own idea, but it is unlikely as design largely remained in the hands of Neville and Anderson, and it serves to subtly challenge and subvert her arguments rather than add meaning to them.

Female Sexuality’, Oz Magazine, July 1970, (p.5).

This trend perpetuated throughout the magazine; a continuation of the approach taken to Widgery’s articles. An article later in the issue by Danae Brook discusses the ‘coming reign of the hermaphrodites’ arguing for greater fluidity between gender roles. 87 Images of aliens and beasts dominate the page with their bright colours drawing attention away from the article itself

86 Figure 9.

87 Figure 10.

28/04/2022 1906893

with their graphic representation undermining the meaning of her arguments (Figure 10). Once again, the imagery and design subverted the more serious messages, forcing the reader to question their reliability. Female energy and engagement were the goal of Oz 29 as it sought to present an alternative to the current attitudes of the WLM, Greer’s arguments have merit, but her radicalism was appropriated by commercial interests. Perhaps recognising their dominant audience, Neville and Anderson oversaw this edition despite Greer’s editorial role and the ideas presented within the magazine were ultimately subverted by its design, limiting their potential.

Greer’s treatment within the underground is further indicative of the failures of her vision, her own nude images would feature in Oz as she was manipulated by its editors under the guise

28/04/2022 1906893

that they too would participate, but after Greer’s photos were taken, they refused.88 This serves as another example of the mockery of Greer’s visions for female sexuality and the manipulation of her attempts to embrace her sexual side. The editors objectified her, using her philosophy for their own gain and demonstrating the reality of female sexual liberation as envisioned by men. The treatment of Greer within the underground press, particularly by those closely linked to Oz, demonstrates the limitations of her vision for female sexuality; without support, Greer’s embracing of her sexuality left her vulnerable to objectification and clearly demonstrates the sexist reality of the version of female sexuality constructed throughout the issues of Oz.

Alternative Approaches: Second-wave feminism

Alternative feminist approaches to Greer confirm this point further, demonstrating the necessity for a new approach outside of the counter-cultural scene and therefore implying the failures of female sexual liberation within it. For radical feminists’, sex was a tool for male domination, and it was therefore necessary to demand full sexual autonomy to be free from patriarchal power. Judith Hole and Ellen Levine, in their book the Rebirth of Feminism, suggested that ‘the sexual revolution which oppresses her (“the liberated woman”) is a revolution made on her behalf by other women, wrestled from men and assented to by them’.89

In this line of thinking, the sexual revolution, when constructed to be acceptable for men, excluded ‘the liberated woman’ (the feminist). This response directly speaks to the feminist rejection of the arguments of Greer, attesting to their view that her approach continued patriarchal assumptions of gender roles and was therefore not sexually liberating. 88 Mary Spongberg, ‘If she’s so great, how come so many pigs dig her? Germaine Greer and the malestream press’, Women’s History Review, 2.3, (2006), 411. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612029300200036 89 Judith Hole and Ellen Levine, Rebirth of Feminism, (NY: Crown Publishing Group, 1971), p. 218.

28/04/2022 1906893

Spare Rib magazine, argued to be ‘one of the most powerful voices of the WLM movement and feminism’, exemplifies this and has been analysed by both Selina Todd and Angela Smith for its feminist approaches to the sexual revolution.90 Smith suggests that the founders of Spare Rib, Rosie Boycott and Sheila Rowbotham, grew frustrated by the inherent sexism within the underground that prevented them from filling any meaningful roles within the press. As a result, they formed their own magazine that sought to challenge the exploitation of women.

This must be considered within the context of ‘consciousness-raising’, a form of activism used by the second-wave feminists’ which sought to critically examine representations of women in images and language within society, it is from this concept that Spare Rib emerged.91 It has largely been asserted that women were drawn to feminism through their rejection of the sexual revolution, particularly as it was constructed within the underground, ‘feminism saw what Greer did not, throughout the sexual revolution, women were still victims of a male constructed sexuality’, the creation of Spare Rib confirms this.92 Rowbotham directly challenged the attempts of Greer, suggesting in response that women ‘could be expressing in our sex life the very essence of our secondariness’.93 By the early 1970s, the new feminist discourse on sexuality had developed a broad critique of permissiveness and its sexual objectification of women.

This dichotomy between pro-sex feminists and anti-pornography feminist is summarised most succinctly by Kate Gleeson as she contends that while Kate Millett was ‘dissecting the misogyny of the works of Norman Mailer and Henry Miller’, Greer was fantasising about their genitalia. 94 Women were drawn to feminism as distinct rejection of the 90 Selina Todd, ‘Models and Menstruation: Spare Rib Magazine, Feminism, Femininity and Pleasure’, Social and Political Thought, 1, (1999); Smith, pp.1-251. 91 Smith, p.5.

92 Spongberg, p.409; for suggestion that women moved to feminism as rejection of sexual revolution see: Smith,

p.14.

93 Sheila Rowbotham, ‘Women: The Struggle for Freedom’, Black Dwarf, (10 January 1969) p.6.

https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/black-dwarf/v13n09-jan-10-1969.pdf [Accessed 13 March

2022]

94Kate Gleeson, “From Suck magazine to Corporate Paedophilia. Feminism and pornography”, Women’s Studies

International Forum, 38, (2013), 83-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2013.02.012

28/04/2022 1906893

sexual revolution as they saw that women were still victims of a male constructed sexuality. Interviews by Green further confirm this as Charles Shaar Murray, a regular contributor to Oz, suggested that ‘the way women were treated on Oz was very influential on Spare Rib and had a lot to do with the founding of post-hippie feminism.’95 Clearly, Spare Rib was a reaction to the underground rather than a development from it, it serves as further evidence of the limitations of the female sexual liberation as it was envisioned by the counter-culture, their rejection of Greer’s vision confirms that she failed to create a ‘genuine sexual revolution’.96

We can see then that attitudes towards women within the underground, although presented as an alternative to ‘straight society’, instead constructed unrealistic sexual expectations for women that were part of the inspiration for second-wave feminism as women such as Rowbotham and Boycott grew frustrated by the patriarchal constraints that persisted even in the culture of the underground. Greer’s contributions and her critics demonstrate the polarised feminist debates, this dissertation has analysed her vision, exemplified in Oz 29, to understand how Greer attempted to create her own ‘counter-cultural woman’ as she envisioned adding autonomy and an identity to the prevailing construction, making her something more than a sexual object.

Ultimately, it has shown that even Greer’s attempts aided in the construction of female sexuality as a commodity for men as Oz editors manipulated Greer’s message to prevent the creation of a ‘liberated woman’ within the counter-culture. The subversion of her visions through imagery and design meant that her feminist issue did little other than further the divide between her and other feminists’ of the period, and her treatment by men formed Greer herself into becoming the ‘hippy chick’ which she condemned. While her philosophy had potential, male interference prevented her vision from becoming a reality.

95 Charles Shaar Murray, cited by Green, Days, p.408.

96 Garton, p.222.

28/04/2022 1906893

Conclusions

Oz magazine attempted to challenge ‘straight society’, envisioning an alternative society which embraced fun and advocated for personal freedoms and sexual liberation. This dissertation has analysed the attitudes towards sexual liberation and the gender politics of the counter-culture through Oz in order to understand the extent of liberation that was achieved. This study adds depth to our understanding of the 1960s and the multiplicity and reality of the sexual revolution that took place. Considering British society as a totality has limited previous considerations of this topic and a focus on the counter-culture allows for a more nuanced understanding of this history.

This study has used Oz magazine as a case study to show how the idealised ‘counter cultural woman’ was constructed, with female sexuality being framed to be more accessible to men, ultimately limiting the extent of female sexual liberation. An analysis of the magazines content, with a recognition of the concept of ‘multimodality’, has demonstrated that every aspect of Oz, from its content to its imagery to its design, aided in this construction.97 Hindsight testimony from editors and contributors to the magazine confirm that it was both pertinent in this period and relevant outside of the pages of the magazine.

A consideration of varying approaches to a sexual revolution that included women, has further confirmed that female sexual liberation as constructed in the counter-culture was limited, as the need for the ‘alternative approach’ of second-wave feminists suggests an inherent problem in the counter-cultural conception of female sexuality. Overall, it has demonstrated that what has been previously seen as a female sexual liberation was in fact a construction of expectations for female sexuality that shaped it within the constraints of the ‘male-gaze’, framing it to become more accessible to men. The ‘counter-cultural woman’ was supposedly free to make

97 Iqani, p.41.

28/04/2022 1906893

her own decisions about her sexuality, yet if she was not available to men then she remained outside of societal acceptability; in this way, the ‘counter-cultural woman’ was no freer than any woman who came before her. The counter-culture attempted to provide a liberated alternative, but in doing so it failed to consider a freer alternative for women. This study has strived to open up a discussion about the reality of sexual liberation within the wider counter-culture, adding to debates about the multiplicity of sexual revolutions as they are experienced. Studies of the movement in America have gone some way to recognising the limitations of the sexual revolution, but in the context of Britain, historians should consider this more thoroughly.

This dissertation has focused only on representations of women; however, it would be pertinent for more rigorous analysis to be undertaken on representations of homosexuality and male sexuality to further expand our understandings of the gender politics of this period. Other magazines may also be considered as Green’s interview with Cassandra Wedd, secretary at INK, suggests that this pattern of sexism was prevalent within other publications as well.98 Oz was chosen for its comprehensive coverage of the opinions of the alternative society, however other underground papers such as It, Private Eye and many more would add depth to this argument furthering historiography on this unique aspect of Britain in the 1960s.

98 Cassandra Wedd, cited by Green, Days, p.369.

28/04/2022 1906893

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

University of Wollongong Archives, ARC 052/48, Oz London Collection (1967-1973).

Available at: https://archivesonline.uow.edu.au/nodes/view/3495:

Oz Magazine, Issue 1, January 1967

Oz Magazine, Issue 2, March 1967

Oz Magazine, Issue 3, March/April 1967

Oz Magazine, Issue 4, May 1967

Oz Magazine, Issue 5, June 1967

Oz Magazine, Issue 6, June 1967

Oz Magazine, Issue 7, October/November 1967

Oz Magazine, Issue 8, January 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 9, February 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 10, March 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 11, April 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 12, May 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 13, June 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 14, August 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 15, October 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 16, November 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 17, December 1968

Oz Magazine, Issue 18, February 1969

Oz Magazine, Issue 19, March 1969

Oz Magazine, Issue 20, April 1969

Oz Magazine, Issue 21, May 1969

Oz Magazine, Issue 22, July 1969

Oz Magazine, Issue 23, August/September 1969

Oz Magazine, Issue 24, October/November 1969

Oz Magazine, Issue 25, December 1969

Oz Magazine, Issue 26, February/March 1970

Oz Magazine, Issue 27, April 1970

Oz Magazine, Issue 28, May 1970

Oz Magazine, Issue 29, July 1970

28/04/2022 1906893

Oz Magazine, Issue 30, October 1970

Oz Magazine, Issue 31, November/December 1970

Oz Magazine, Issue 32, January 1971

Oz Magazine, Issue 33, February/March 1971

Oz Magazine, Issue 34, April 1971

Oz Magazine, Issue 35, May 1971

Oz Magazine, Issue 36, July 1971

Oz Magazine, Issue 37, September 1971

Oz Magazine, Issue 38, November 1971

Oz Magazine, Issue 39, December 1971

Oz Magazine, Issue 40, February 1972

Oz Magazine, Issue 41, April 1972

Oz Magazine, Issue 42, May/June 1972

Oz Magazine, Issue 43, July/August 1972

Oz Magazine, Issue 44, September 1972

Oz Magazine, Issue 45, November 1972

Oz Magazine, Issue 46, January/February 1973

Oz Magazine, Issue 47, April 1973

Oz Magazine, Issue 48, November 1973

Other Underground Publications:

IT Magazine, Issue 48, 31

January 1969, International Times Archives

https://www.internationaltimes.it/archive/index.php?year=1969&volume=IT-Volume

1&issue=49 [Accessed 28 March 2022]

Rowbotham, Sheila, ‘Women: The Struggle for Freedom’, Black Dwarf, (10 January 1969)

https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/black-dwarf/v13n09-jan-10-1969.pdf

[Accessed 13 March 2022]

London, British Library, Spare Rib Magazine Collection, Spare Rib, Issue 1, July 1972

Contemporary Works:

Hole, Judith, and Ellen Levine, Rebirth of Feminism, (NY: Crown Publishing Group, 1971)

Greer, Germaine, The Female Eunuch, (Glasgow: HarperCollins, 1970)

Millett, Kate, Sexual Politics. (NY: Garden City, 1970)

28/04/2022 1906893

Neville, Richard, Play Power, (London: Jonathan Cape, 1970)

Jonathon Green’s Interviews:

Lane, Nicola. Cited by Jonathon Green in Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground 1961-1971, (Reading: Cox and Wyman, 1988)

Morris, Keith, cited by Jonathon Green in Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground 1961-1971, (Reading: Cox and Wyman, 1988)

Murray, Charles Shaar, cited by Jonathon Green in Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground 1961-1971, (Reading: Cox and Wyman, 1988)

Wedd, Cassandra, cited by Jonathon Green in Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground 1961-1971, (Reading: Cox and Wyman, 1988)

Rowe, Marsha, cited by Jonathon Green in Days in the Life: Voices from the English Underground 1961-1971, (Reading: Cox and Wyman, 1988)

Secondary Sources:

Books:

Allyn, David, Make Love, Not War: The Sexual Revolution an Unfettered History, (London: Routledge, 2000)

Atton, Chris, ‘Counter-culture and Underground’ in eds. Andrew Nash et al. The Book in Britain, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019) Ebook

Birch, James, and Barry Miles, The British Underground Press of the Sixties, (London: Rocket 88 Books, 2017)

Carlin, Gerry, ‘Rupert Bare: Art, Obscenity and the Oz trial’ in ed. Marcus Collins, The Permissive Society and Its Enemies, (London: River Oram Press, 2007)

Cook, Hera, The Long Sexual Revolution: English women, sex, and contraception 1800-1975, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Cook, Matt, ‘Sexual Revolution(s) in Britain’ in eds. Gert Hekma and Alain Giami, Sexual Revolutions, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

Collins, Marcus, Modern Love, (London: Atlantic Books, 2004)

Franklyn, George, The Failure of the Sexual Revolution, (London: Open Press Gate, 2003)

Fountain, Nigel, Underground: The London Alternative Press, 1966-1974, (London: Routledge, 1988)

28/04/2022 1906893

Gatlin, Rochelle, ‘Women and the 1960s Counter-culture’, in American Women since 1945, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1987) Ebook

Garton, Stephen, Histories of Sexuality, (London: Routledge, 2004) Ebook

Gauntlett, David, Media, Gender and Identity, (London: Routledge, 2008) Green, Jonathon, All Dressed Up: Sixties and the Counterculture (London: Jonathan Cape, 1998)

Goldfield, Evelyn, Sue Munaker, and Naomi Weisstein, ‘A Woman is a Sometime Thing’, in ed. Priscilla Long, The New Left; a Collection of Essays, (Boston: P. Sargent, 1969).

Hall, Lesley. Sex, Gender and Social Change in Britain since 1800, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000)

Iqani, Mehita, Consumer culture and the media, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012)

Jeffreys, Sheila, Anticlimax: a feminist perspective on the sexual revolution, (NY: Washington Square, 1991)

Marwick, Arthur, ‘Youth Culture and the Cultural Revolution of the Long Sixties’, in The Sixties, (London: Bloomsbury Reader, 2012)

McLuhan, Marshall, Understanding Media: The extensions of man, (NY: McGraw-Hill, 1964)

Mort, Frank, Capital Affairs, (London: Yale University Press, 2010)

Nead, Lynda, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality, (London: Routledge, 1992). Ebook

Nelson, Elizabeth, British Counter-Culture 1966-73: A Study of the Underground Press, (London: Macmillan Press, 1989) Ebook

Nicholson, Virginia, How was it for you?: Women, Sex. Love and Power in the 1960’s, (Harlow: Penguin Books, 2020)

Palmer, Tony, The Trials of Oz: The Longest Obscenity Trial in History, (London: Lume Books, 2021)

Reynolds, Chelsea, ‘The “Woke” Sexual Discourse’ in ed. Miglena Sternadori and Tim Holmes, The Handbook of Magazine Studies, (New Jersey: Blackwell, 2020) Ebook

Roszak, Theodore, The Making of a Counterculture, (London: Faber and Faber, 1970)

Rycroft, Simon, Swinging City: A Cultural Geography of London, 1950-1974, (London: Routledge, 2011) Ebook

Sandbrook, Dominic, White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties, (NY: Little, Brown And Company, 2006)

28/04/2022 1906893

Smith, Angela, Rereading Spare Rib, (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017) Ebook

Weeks, Jeffrey, Sex, politics and society: the regulation of sexuality since 1800, (NY: Routledge, 1989)

Journal Articles:

Anderson, Jim, ‘Remarks on 1968, Richard Neville and his book’, Counterculture Studies, 2.1, (2019) DOI: 10.14453/ ccs.v2.i1.13

Bailey, Dr. Joanne, ‘Is the rise of gender history “hiding” women from history once again?’, History in Focus, 8, (2005) https://archives.history.ac.uk/history-in-focus/Gender/articles.html [Accessed 25 March 2022]

Baker, Phil, ‘The British Underground Press of the Sixties’, Times Literary Supplement, 6006, (2018)

link.gale.com/apps/doc/A634285451/AONE?u=univbri&sid=googleScholar&xid=cb001d64

[Accessed 18 February 2022]

Baumeister, Roy F., and Jean M. Twenge, ‘Cultural Suppression of Female Sexuality’, Review of General Psychology, 6.2, (2002) DOI:10.1037//1089-2680.6.2.166

Brennan, AnnMarie, ‘An Architecture for the Mind: Oz Magazine and the Technologies of the Counterculture’,

Journal of DOI:10.1080/17547075.2017.1368828 Design Studies Forum, 9.3 (2017).

Bousalis, Rina R, ‘The Counterculture Generation: Idolized, Appropriated and Misunderstood’, The Councilor, 82.2, (2021) https://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor/vol82/iss2/3 [Accessed 3 March 2022]

Buckingham, David, ‘Children of the Revolution? The counter-culture, the idea of childhood and the case of Schoolkids Oz’, Strenæ online, 13, (2018). https://doi.org/10.4000/strenae.1808 Cook, Hera, ‘The English Sexual Revolution: Technology and Social Change’, History Workshop Journal, 59, (2005)

Collins, Marcus, ‘Permissiveness on Trial: Sex, Drugs, the Rolling Stones and the Sixties

Counterculture’, Popular Music https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2018.1439295 and

Society, 42.2, (2019)

Daly, Rebecca, ‘With energy, ideas and cheek to spare, Richard Neville was the boy of OZ’

The Conversation, 6, (2016) https://ro.uow.edu.au/asdpapers/558 [Accessed 11 February 2021]

Frazer, Philip, ‘Alternate and Underground Press – 1968, Counterculture, Protest, Revolution

conference’, 2.1, (2019) http://dx.doi.org/10.14453/ccs.v2.i1.7

Gleeson, Kate, ‘From Suck magazine to Corporate Paedophilia. Feminism and pornography’,